People of Hope

Christians are people of hope. That is one of our distinguishing marks. Perhaps we don’t normally think of ourselves like that. Others think of Catholics as people who do, or don’t do, certain things – like eating fish on Fridays, not having an abortion – or who believe, or don’t believe, certain things – like purgatory or venerating Our Lady. And that of course is true. But do we think of ourselves as people of hope? Are we noticeably hopeful people?

In the second reading today St Peter says that we should always have an answer ready ‘for people who ask you the reason for the hope that is in you’. He evidently thought that hope was a mark of Christian believers, and that this was noticed and remarked on by unbelievers, not least by those who slander and accuse them. That’s why he says we should give our answer with courtesy and respect. That is more likely to be heard than an angry or dismissive response. What is this ‘hope that is in us’? And how would it differ from the prevailing attitude of non–believers?

The first thing to say is that our hope is not based on any of the pleasant things that may happen to us. Instead it is based entirely on God, not on ourselves or on anything in the present world. It springs from a profound conviction that God will bring us to the fulfilment he intends for us – unless we exclude ourselves by our own deliberate fault. After all, God has created us for our happiness, not for his own convenience. So we can have unshakable trust in his loving purpose for us. That is the one supreme thing that we can all look forward to. In contrast, many people have no sense of the love of God as giving value and purpose to life.

Despite this, many people are ready to show real heroism and self-sacrifice. Hope features prominently in the New Testament. St Paul talks about ‘faith, hope and love’, and says that ‘hope does not disappoint us because the love of God has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit which he has given us’. But the really remarkable thing is the place that hope has in the Old Testament. Even without a clear belief in an afterlife, the children of Israel trusted that God would fulfil his loving purposes for them, just because he was God, certainly not because they deserved it. ‘O Israel, hope in the Lord; for with him is plenteous redemption’.

We call this hope a ‘theological virtue’, which is the technical term for a disposition in us which is given directly by God, not in any way produced by ourselves: virtues like justice or fortitude or prudence we can develop in ourselves by our choices and actions; you become a prudent person by behaving prudently. But there is no way we can set our hope in God unless God himself enables us to do so. Hope is God’s gift to us, based on his loving purposes for our good, made clear to us in Christ. But we can of course open our hearts more and more to God so that the Spirit will make faith, hope and love grow in us.

From this two conclusions follow. First, the virtue of hope has nothing to do with optimism. Optimism is a temperamental quality. Some people are naturally optimistic; others are like Thomas the Apostle, always expecting the worst. Christian hope is not temperamental; it has nothing to do with trusting to luck, or with a vague wishy-washy feeling that ‘everything will turn out all right’. Hope depends on what we know about God by faith, and on our tenacity in holding on to this. Second, hope can persist along with almost unimaginable suffering, disappointment and disaster. You can see this in the fortitude of the martyrs. I was reading recently about the extreme torture suffered by the Jesuit Robert Southwell in the 16th century, which he bore with astonishing faith and hope. But it is shown above all in Christ on the cross. Despite the agony and the sense of abandonment by God, he still cried out; ‘Father, into your hands I commend my spirit’.

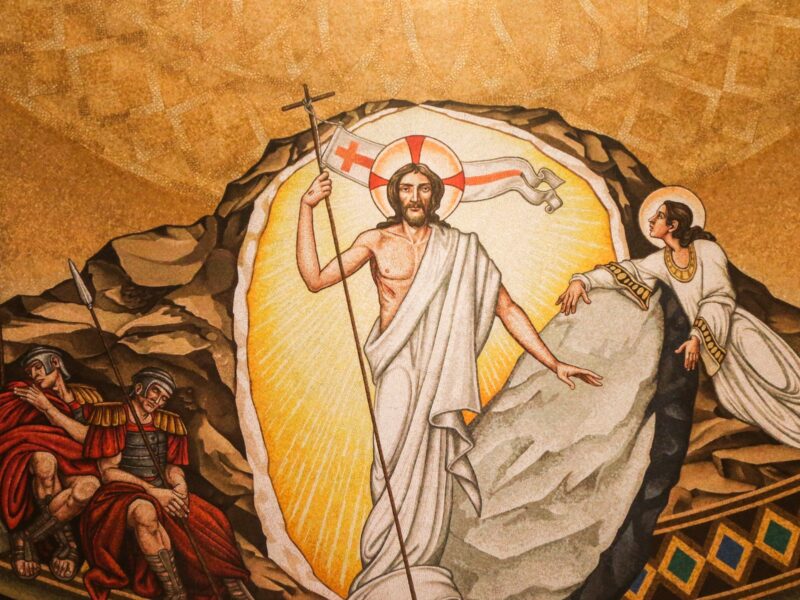

Hope is not based on what is happening to you in the here-and-now, nor on what you might be able to do or receive in the future. It is based entirely on God, on our certainty that we are loved by God because he has said so, and also on the resurrection of Christ. If Christ is not risen then our faith and hope are in vain. Perhaps few of us are called to heroic levels of suffering. But sickness, disappointment, bereavement, and the gradual weakening that comes with old age can be quite testing enough. That is one point at which we all need the virtue of hope.

So, as Eastertide draws to its close, perhaps it is a good time to ask ourselves: Do I really have hope? Am I a person of hope? And we can remind ourselves that this hope does not depend on us, on our strength and determination, but wholly on God’s love for us in Christ, shown in his Resurrection.