Sanctifying the Family

Feast of the Holy Family | Deacon Samuel Burke considers the sanctifying effect of Christ on the relationships within the Holy Family.

Over the last few weeks you will have, almost certainly, seen many depictions of the Holy Family. Perhaps you saw Jesus, Mary and Joseph on Christmas cards, or perhaps in Crib scenes, or perhaps you were lucky enough to see them in action at a children’s Nativity play?! Each depiction whilst telling the same essential story, conveys something slightly different, putting the accent on a different aspect of a story at times dangerously familiar. There’s variety, too, in the many beautiful paintings of the Holy Family, the Great Masters down, where we them in almost every conceivable geographic, climatic, racial, economic, and cultural setting. It is almost as if the Holy Family carry a kind of ‘everyman’ quality, as it were; standing outside of time.

And yet, don’t the Gospels tell us that Jesus was born in a particular place, Bethlehem; and, at a particular time, in the reign of Caesar Augustus just over two thousand years ago? How can we allow — let alone celebrate — the various renderings of the Holy Family which are apparently at odds with one another, to say nothing of the historical reality? Reflecting on this question, G. K. Chesterton once wryly observed: “No man who understands Christianity will complain that [such paintings] are different from each other and different from the truth, or rather the fact. It is the whole point of the story that it happened in one particular human place that might have been any particular human place; a sunny colonnade in Italy or a snow-laden cottage in Sussex.”

Certainly, the Holy Family were very much in time, as the Gospels attest. But in another sense they stand beyond it because the Holy Family carries an enduring significance, a universal meaning. It’s not simply about membership, central though that is –no Christ, no Holy Family! But on this feast, we are invited to consider their interaction, their family relationship together, best described perhaps as a communion of love. This communion of love speaks to the human-social aspect of the Incarnation. The Word became flesh, and dwelt among us. That dwelling was, for the greater portion of Christ’s life, with His family. By His very presence He sanctified that family and for this reason, we rightly call it ‘holy’. As such, the Holy Family stands as a beacon, a model for all of us to imitate; we should follow them in practicing the virtues of family life. That’s easier said than done, of course.

One reason it’s difficult lies in the fact that we’re told very little about the Holy Family in Sacred Scripture. Amongst the scant “infancy narratives” which we do have is St. Luke’s unique account of the Presentation. We’re told that Jesus, Mary and Joseph have travelled to the Temple for purification and to make sacrifice in accordance with the Mosaic Law. Even though the Holy Family includes the infant Son of God, nevertheless they follow the Law. So from the very outset, we see that Jesus came not to abolish the law but to fulfil it.

Against this backdrop we’re introduced to old Simeon. He had been waiting for the “Messiah” and the aged prophet recognises Him in his midst. The first poetic part of Simeon’s speech, which we sing every night at Compline, bears eloquent testimony to the coming of the Messiah, not only as the fulfilment of the promises made to Israel but as the light for all nations. Understandably, this leaves Mary and Joseph in some bemusement. How could Simeon know all this, even if they themselves did? The prophetess Anna later makes similar praises, presumably no less astounding for Jesus’ bewildered parents? But the second part of what Simeon says, addressed to Mary, is a foreboding prophecy: a sword would pierce Mary’s heart. This wound alludes to the Christ’s Passion and Death. A wound arrestingly visible in Michelangelo’s Pietà. A wound not due to any fault on Mary’s part but explained only vicariously by that division we all know within us, by the initial wound of our fallen humanity that marks us still: original sin. The Holy Family may have been perfect or close to it, but they suffered the ultimate tragedy for Christ’s sacrifice was also theirs.

It’s not only in our experience of tragedy that we can come closer to the Holy Family but also in their shared humanity, and through some reflection on their life together even amidst paucity of detail, amidst relative silence. We can picture, if we try, the Holy Family in Nazareth in quiet domesticity; working; following the Law; praying; and above all, loving. Prayer on these themes, not without some imagination, can lead us to greater heights. And, just like great artists, we can strive to make this “School of Nazareth” where we grow in virtue and deeper friendship with Jesus somehow our own, striving to work their example into our lives whether that indeed be “on a sunny colonnade in Italy or a snow-laden cottage in Sussex”.

Genesis 15:1-6, 21:1-3 | Colossians 3:12-21 | Luke 2:22-40

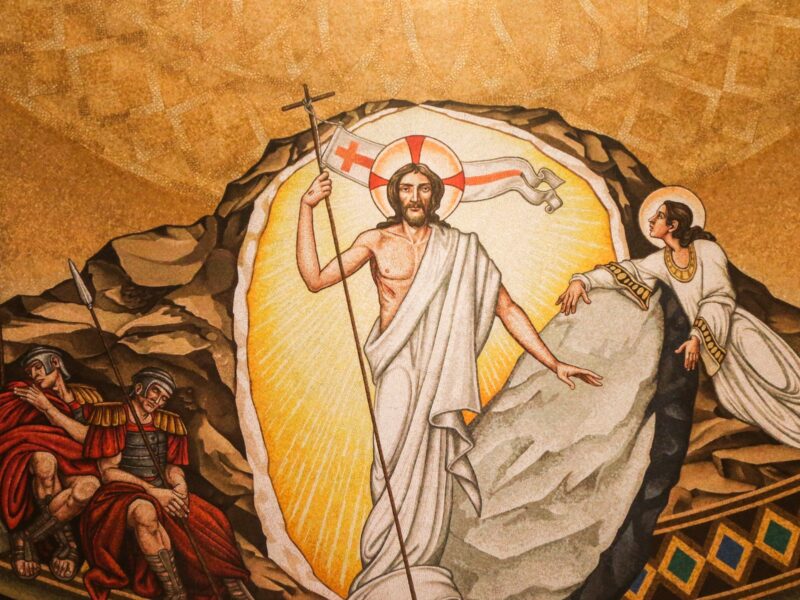

Photograph by Fr Lawrence Lew OP of the Presentation mosaic in the Rosary Basilica, Lourdes.