The Three Herods

Palm Sunday of the Passion of the Lord. fr Peter Harries contrasts the Kingship of Jesus with that of the three Herods we find in Scripture.

I don’t think I have ever heard a sermon on Palm Sunday, so it is rather odd preparing one. Palm Sunday has the longest liturgy of any Sunday of the year apart from the Easter Vigil. The procession with palms and the devout listening to the passion of our Lord both preach most eloquently. But I will try to say something by concentrating on a single episode told only by Luke, for this year we read Luke’s account of the passion.

Luke tells us that after hearing the accusations against Jesus, but before the conclusion of the trial, Pilate sent Jesus to Herod to see what Herod would make of Jesus. Herod the Tetrarch, the political ruler of Galilee was in Jerusalem for the Passover feast. The scholars universally suggest that Herod’s attendance was for political show rather than any genuine devotion.

There were three Herods, all of the same ruling dynasty, all mentioned in the New Testament, though Luke does not make this clear and I suspect most Christians, then and now, assume there was only one nasty Herod. First there was King Herod the Great, a ruler with a blood-thirsty reputation. He was King when Jesus was born. He welcomed the magi to Jerusalem and then schemed to kill baby Jesus and did manage to kill the Holy Innocents. Herod the Tetrarch, also know as Herod Antipas, was a younger son of Herod the Great. This second Herod, the Tetrarch, was never actually a king, and had inherited only Galilee, an unimportant part of his father’s kingdom. He ruled it ruthlessly, raising taxes and suppressing all dissent for over thirty years, before Jesus was brought before him in Jerusalem. Jesus referred to him elsewhere in the gospel, as a fox. He would fall from power, like Pilate, a few years later. A third Herod, Herod Agrippa, yet another member of the dynasty, participated in the trail of St.Paul, which Luke records later in Acts. All three Herods were ruthless and adept political schemers, well known to the imperial family in distant Rome and tolerated because they meet the insatiable imperial financial demands. They also managed usually to keep in with the various Jewish religious authorities, the Sadducees and Pharisees and others in Jerusalem and so minimized open religious conflict in their territories.

Herod the Tetrarch had heard about Jesus, but this was their only recorded meeting. Herod had recently killed John the Baptist. Herod knew that many of John’s followers now looked to Jesus. But who was Jesus, and most importantly, did Jesus threaten Herod’s authority and his well-known ambition to be King of the Jews like his father? So Herod interrogated Jesus at length, asking him many questions. The chief priests and the scribes were present, egging Herod on, keeping up the pressure against Jesus, trying to force the issue. Herod also seems to have been a volatile character, with rapid mood swings. First he seeks to work out who Jesus actually is, with perhaps genuine questions. Then he switches, and joins his bodyguards in physically abusing Jesus, mockingly clothing Jesus in an elegant (?royal) robe, and then sends him back to Pilate for judgment, and deferring to Herod’s authority. So, Luke tells us most pointedly, Herod becomes friends with Pilate, no clash of jurisdiction here.

Neither Pilate nor Herod, neither the Jewish nor Roman political authorities want to condemn Jesus. They knew that Jesus was not an immediate political threat, he was not a violent rebel. Yet Herod and Pilate, both unscrupulous political operators, become friends by co-operating in the plot by the religious authorities to kill Jesus. Those who done much evil find themselves swept along, unable to defend Jesus’ innocence against his enemies.

Perhaps Herod can be a counter-example for us. If we are always seeking our own advantage, in family, financial or even religious issues, then we end up only being able to think of ourselves. Integrity and mercy are values, virtues that we are then unable to live.

God has allowed Herod and Pilate to act according to their corrupted nature, a nature they have chosen and embraced. So Jesus is condemned to death on the cross. God in his mercy allows this death, so that Jesus might rise, that God might have mercy on us, who believe and hoped in mercy and not short-sightedly in self-promotion and self-preservation.

Readings: Luke 19:28-40|Isaiah 50:4-7|Philippians 2:6-11|Luke 22:14-23:56

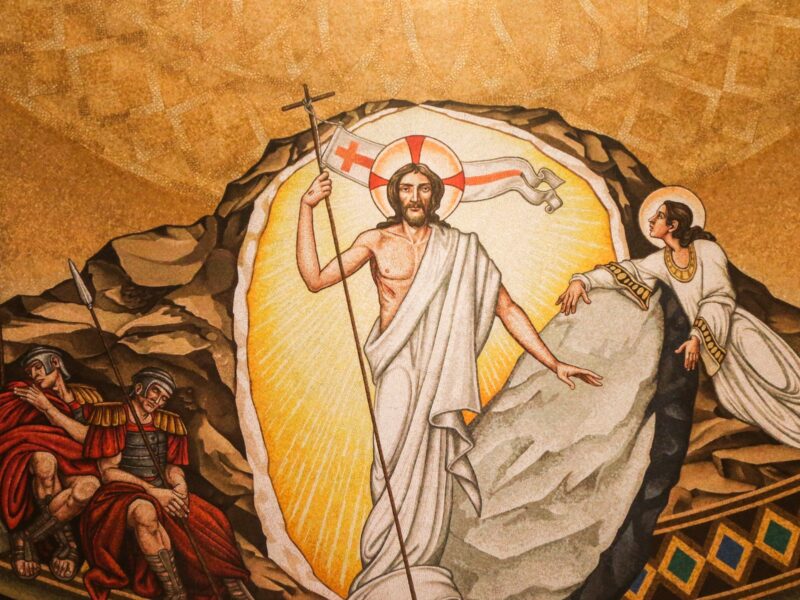

The image above is a medieval stone carving from the Cloisters Museum in New York.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

A Website Visitor

Thank you for today’s homily. You have answered a question in my mind for many years about Herod -I did not know there were three yet logic told me there must be more than one! This was interesting and informative. Bless you in your endeavours to inform and teach us. M.

A Website Visitor

Most illuminating! Thank you!

A Website Visitor

A powerful reflection indeed. I have personally learnt a lot from this reflection. God bless you

A Website Visitor

Magnificent & very informative in its exegesis and historical setting. But as you say, the Palm Sunday liturgy is long . . . Perhaps I’ll save most of it – in fragments – for feeding minds & souls later in the week! Thank you Have a Holy Week and a Happy Easter db