Tuesday of the Fifth Week of Lent: Snakes on the Plain

Thankfully, we’re fairly unlikely to find ourselves surrounded by venomous snakes of the literal variety. Nonetheless, we too are surrounded by the chaos wrought by the first serpent, the tempter of Genesis 3, through whose enticements suffering, sin and death first entered the world. If we could take a step outside the ‘fourth wall’ and view the cycle of sin and suffering from God’s perspective, I imagine that at times we’d look as chaotic as the panic-stricken passengers of Snakes on a Plane. But try as we might to avoid getting contaminated by sin (like the passenger “Three Gs”, who refuses even to touch another person without sanitising his hands), we are inevitably bound up in a world scourged and damaged by our sins and those of our fellow sojourners. Whereas the passengers try to simply hide themselves from the threat (Flynn announces “We need to put a barrier between us and the snakes!”), what is really needed is not only an anti-venom but an ultimate defeat. Salvation must break in from outside the cycles of sin, but it must also break out from inside: what is needed is the incarnation, God’s entry into human history without contamination by sin, opening the life of God to man and the life of man to God.

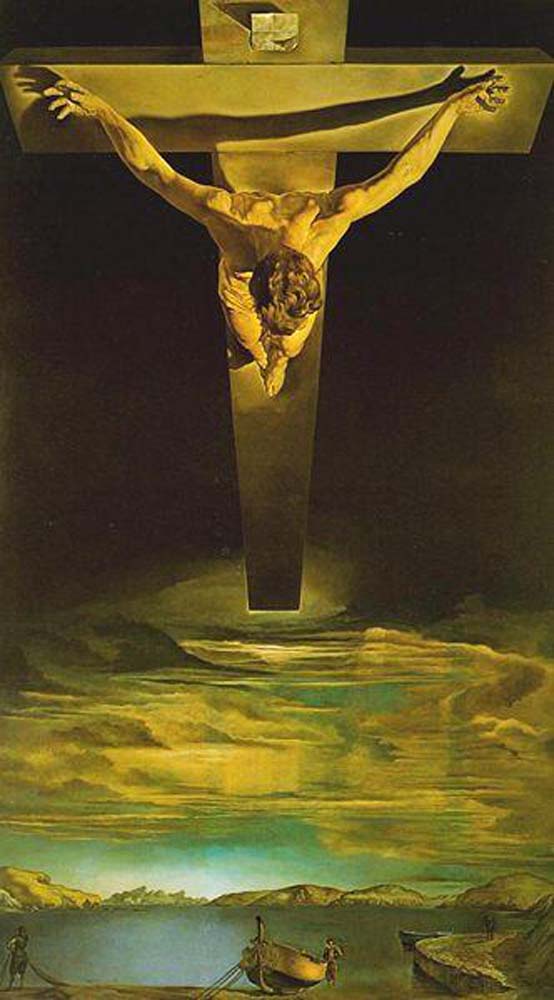

Indeed, as St. John stresses in today’s gospel, God – who stands over and against all the chaotic structures of sin and human disorder – has intervened to lift up for humanity a definitive sign of salvation: his own crucified son, a sign that both points forward to the life of the world to come, and makes that life possible by opening up for us a route out of self-destruction. Whereas the Israelites cast their eyes on the serpent made of molten precious metal, we look to a crucified man as the sign of our hope: the crucified God-man, lifted up before our eyes on the cross, rejected and despised, devalued and discarded.

Indeed, as St. John stresses in today’s gospel, God – who stands over and against all the chaotic structures of sin and human disorder – has intervened to lift up for humanity a definitive sign of salvation: his own crucified son, a sign that both points forward to the life of the world to come, and makes that life possible by opening up for us a route out of self-destruction. Whereas the Israelites cast their eyes on the serpent made of molten precious metal, we look to a crucified man as the sign of our hope: the crucified God-man, lifted up before our eyes on the cross, rejected and despised, devalued and discarded.